A few days ago we finally got our planning permission. Now we are confident to continue with some of the more serious part of the conversion. Hooray! I’ll decorate this post with some non-standard buildings that are for sale in Germany today, because looking at possibilities is always exciting and fun. Click on the pictures to see the respective ads with more photos.

Through all of our searches online, we never managed to find a “how-to” for converting a building to residential use here in Germany. There’s no information regarding this sort of case on the various Bauamt (Building Inspector’s Office) websites around, since it’s a too rare an occurrence for any Beamter (bureaucrat) to bother writing any. What follows are the steps we had to take. Since our building isn’t listed as a historical building, we have no experience with Denkmalschutz.

- A different NAK church for sale in Dortmund.

Obligatory disclaimer: What follows is not advice, nor should it be taken as such, and we take no responsibility for any lack of accuracy in the steps. It is only a list of the steps we had to take, in our particular Land (state), and our particular Gemeinde (district), and for our particular building. If you have a similar building for conversion, please consult your architect, local Bauamt, and real estate attorney/notary.

Our case was relatively simple. We planned no major structural changes immediately, the house is in a residential neighborhood, already had heating, and our building is not listed under Denkmalgeschütz. We do know that if you do have a listed building, you have plenty of tax write-off capabilities and subsidies at your disposal, but you also have to follow some rules and dictates of the local protected building office, which complicate matters greatly.

Once we found a suitable building, we followed the following steps:

- In the process of due diligence, we made an informal inquiry at the Bauamt by phone to see if they would have any obvious objections to our plans. Since the building we were considering stands in a residential neighborhood already, and we weren’t planning on making drastic changes, we were told objections were highly unlikely.

- Hire an architect. You must have an architect who is a member of an appropriate board of architects to co-sign some of the necessary documents in the planning application. While this might sound unnecessary, we found you can’t skip this step. Our architect also provided quite a lot of peace of mind and invaluable advice, so even if it weren’t required, I’d have hired an architect anyway.

- Negotiate your price and buy the building. There are plenty of resources on the web that explain the German process in English, so I won’t dwell on that here.

In short, once the parties agree on a price, they agree to hire the services of a Notar – a contract lawyer who serves as an impartial intermediary between the buyer and seller. The seller (should) send the Notar the page number in the Grundbuch (register of deeds) of the building. The Notar gets an official copy of the deed, and uses it to draw up a contract, which he then sends to the parties to read. The buy should at this point check with the local Bauamt if there are any Baulasten (liens) on the property. In our case, this could be done easily online. The parties then make a date to officially read and sign the contract. Note that the parties can legally back out of the deal at any point up until the signing of the contract! (…which happened to us previously, as I noted in The Search).

If any one of the parties has weak German skills, the services of a translator have to be hired for the contract reading. Fortunately, my German is good enough that we avoided that expense. The notary reads the contract out loud, then the parties sign.

The buyer then pays the deed tax, and sends proof of this to the notary. The notary then has the Grundbuchamt (Deed office) enter the name of the buyer as first in line to buy the property. Once that change is confirmed, money changes hands. When the seller confirms that he has been paid, the notary has the Grundbuchamt change the official owner of the property, and the buyer gets the keys and all associated documents within a set amount of time. The buyer pays the notary.

- The architect draws up the plans noting any changes, and files the form for a simplified Baugenehmigung (construction permit) to get the Nutzungsänderung (change of purpose). This point was very confusing at first. For the most part, the changes we want to make would not necessitate applying for a Baugenehmigung – those are generally only needed for serious structural changes. There’s no dedicated form for Nutzungsänderung, and it’s not at all obvious that one should use this form out of all the ones out there.

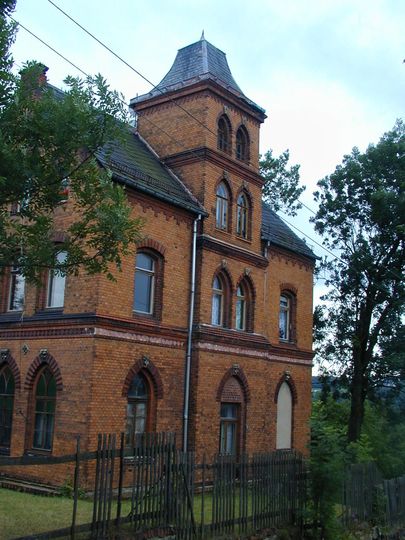

Despite appearances, this is not a church. It's a former city hall in a small town in the Rheinland-Palatinate.

- Move in, if that’s possible. You don’t need the Nutzungsanderung to be cleared to be able to move into the house, or really for any of the steps for everyday life. You can move in if you can provide yourself kitchen and bathroom facilities.

- Arrange for services as needed. We ordered trash collection with no problem. Getting a phone connection was much more exciting (and for a separate post), but the problems had more to do with inefficiency than with our odd situation.

- Register your residence. This step was a little awkward since our new address wasn’t in the list of residential addresses when we tried to register, and the ladies at the Meldeamt weren’t sure what to do with us. It turns out that you really can register at a not-yet-officially-residential address so long as the planning application process has been started. After a few calls back and forth, we could register.

- Supply more documents for the planning permission application. We hoped to avoid having to hire a structural engineer at this point, but the Bauamt decided that they wanted to see calculations now for structure, noise, and insulation. We had to quickly find an engineer (Statiker) that could provide us with a document that everything looks ok according to applicable norms. We were very lucky that the house already had heating, since this eased the standards we have to meet. If we had to install heating where there was none, then we would have to insulate to an extremely hard standard. We also took out the plan for a garage for now. Apparently, the bureaucrats do a lot of garage permissions, and when they saw “garage” on our plans, they leaped at the chance to be annoying. We haven’t thought through the garage idea in any detail, and it’s got a low priority. We just know that eventually we’ll want one in the back corner of the property. Since they started to ask about nonsense like roofing material and exact sizes and so forth, we just dropped it for now. We’ll apply for permission for that separately.

All in all, the process took about two months. We didn’t have any serious problems, and we were fairly confident the whole way through that we’d get the permission in the end. Going through this process, we saw that we were lucky in our choice of building. If we had decided on another type of building, like a factory or warehouse, or something not in a residential area, then we might have had some headaches bringing the insulation or other things up to code. Dumb luck is a nice thing sometimes.

I’ll close with a few more pictures of buildings currently for sale that would have to be converted, which aren’t churches.

© 2011 – 2012, Converting a Church. All rights reserved.